In June 2021, President Biden signed Executive Order 14035 to advance diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility in the Federal workforce. This order called for an evaluation and expansion of Federal employment opportunities for formerly incarcerated persons.

Before this executive order, in fiscal year (FY) 2020, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) formed a task force to identify vulnerable workers and determine ways to better serve them. The EEOC identified formerly incarcerated persons as one category of vulnerable workers due to the challenges they face in securing employment after their incarceration. In the FY 2017-2021 Strategic Enforcement Plan, the EEOC identified the use of background checks related to arrest and conviction records as among its national substantive area priorities because African Americans and Latinos are disproportionately incarcerated.

This report comes from the EEOC’s Reports and Evaluations Division at the Office of Federal Operations (OFO). It asks two related questions:

1) How likely are people with prior arrests or convictions to work in the Federal sector?

2) Could regulating the timing of background checks during the recruitment process (e.g., ban-the-box policies) protect those applicants with a prior arrest or conviction from discrimination?

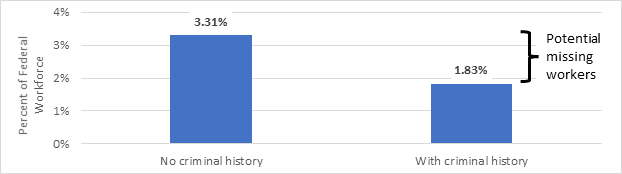

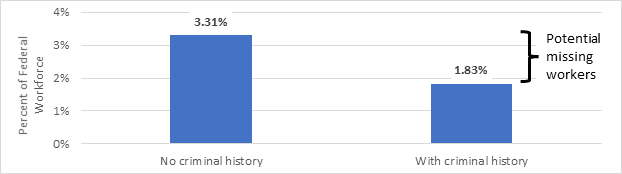

In answering the first question, this report first notes the lack of systematic data collection tracking employment outcomes for workers with prior records of incarceration. Using a nationally representative survey with data from 2003 through 2017, this report finds that people with prior records were nearly half as likely to be Federally employed compared to those without such records. This gap suggests that there were roughly 300,000 fewer previously formerly incarcerated workers in the Federal workforce than expected.

The current study does not have sufficient data to fully assess the causes of lower rates of Federal employment for individuals with a history of incarceration during the 2003 to 2017 time period. For instance, it is possible that people with incarceration records erroneously believe they are barred from Federal employment and self-select out of the applicant pool. It is also possible that hiring managers are less likely to hire applicants with any kind of record -incarceration, arrest, or conviction. Additional research directly examining the hiring practices of Federal agencies towards workers with a record is necessary to better understand how employment for these community members could be increased.

The lack of available data constrains the ability to measure Federal employment for workers with conviction, arrest, or incarceration records. Therefore, one high-value policy change would be to track the number of Federal workers with arrest or conviction records over time. Existing data could be leveraged to generate such a measure. For example, researchers could use data from the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency (DCSA)—the central processor of background investigations for the Federal government—to determine the proportion of Federal employees that had a background check return an arrest or conviction record. [1] Tracking this statistic over time would allow the EEOC and other Federal agencies to assess how successful different policies and procedures are in expanding Federal employment opportunities to formerly incarcerated persons. The EEOC should coordinate with the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) and the DCSA to gather data on suitability adjudications, with a focus on the characteristics of applicants whom employers deem to be appropriate to hire for a given position.

To answer the second question, this study looks to lessons learned from outside the Federal sector. Researchers examined data on complaints filed with the EEOC where complainants alleged that their past exposure to the criminal legal system was improperly adjudicated. The results show that so-called ban-the-box policies, which generally prohibit criminal background checks until after a conditional job offer is made, led to significantly more and more meritorious complaints filed per month. Specifically, ban-the-box policies made it more likely that investigators were able to find enough evidence to proceed further in the complaint process. Without additional data and analysis, it is difficult to determine the exact cause behind these results. It is possible that, after ban-the-box timing restrictions were imposed, employers engaged in more discrimination based on arrest and conviction records. However, it may also be the case that applicants were more aware of their protections after timing restrictions were implemented.

Title 5 of the Code of Federal Regulations regarding Recruitment, Selection, and Placement (General) and Suitability (5 CFR parts 330 and 731) prohibit Federal employers from collecting criminal history information, unless an exception has been granted until after until after a conditional job offer has been made and accepted. [2] The analysis presented in this study suggests that such a policy may be helpful in enforcing Title VII and should be continued. These recruitment rules were expanded to Federal contractors in December 2021, which may improve Title VII monitoring and enforcement even more. [3]

To ensure adherence to best practices, recruiters should follow these rules and regulations, and the EEOC should conduct follow-up research to ensure Federal employers are following best practices. Applicants should also be made aware of their rights regarding the accuracy of background checks and the appropriate uses of arrest and conviction records in employment decisions.

In June 2021, President Biden signed Executive Order (EO) 14035 to advance diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility in the Federal workforce. This order called for an evaluation and expansion of Federal employment opportunities for formerly incarcerated persons (Executive Order No. 14035, 2021).

Even before EO 14035 was issued, in Fall 2019, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) formed a task force to identify vulnerable workers and determine ways to better serve them. Formerly incarcerated persons were among those identified as vulnerable workers due to their difficulty in securing employment after their incarceration, which includes pre-trial detention and post-conviction incarceration. The task force built upon 2012 guidance on the use of arrest and conviction records in employment decisions. Furthermore, because Black and Latino people are disproportionately incarcerated, the EEOC identified the use of criminal background checks as among its national substantive area priorities in the FY 2017-2021 Strategic Enforcement Plan. The analysis contained throughout this report assesses Federal employment for formerly incarcerated people and the policies that promote or frustrate Federal work for these community members.

Prior incarceration impacts many U.S. citizens’ abilities to find employment. When formerly incarcerated community members find stable jobs, they promote public safety and break cycles of economic hardship for future generations of Americans. Yet in 2017, 622,400 people were released from state and Federal prisons (Bronson, 2019), and many of them faced challenges reentering the workforce (Couloute & Kopf, 2018). Additionally, the costs imposed by the judicial system are not borne equally by all. Research estimates that 8 percent of all adults and one-third (33 percent) of African American men had a felony record as of 2010 (Shannon et al., 2017). Another study found that African American adults were nearly 6 times more likely to be incarcerated than White adults in 2018, while Hispanic adults were about 3 times as likely to be incarcerated compared to White adults (The Sentencing Project, 2018). These data likely represent a conservative estimate of racial disparities in the criminal legal system given that the studies described above do not include individuals who were arrested or convicted but did not serve time in jail or prison for a felony.

Substantial evidence suggests that applicants with arrest or conviction records face many barriers to employment. For example, individuals with arrest or conviction records have much lower employment rates than those without these records. [4] Mueller-Smith and Schnepel (2021) found that, for first-time felony defendants, avoiding a felony conviction through diversion (i.e., wherein public officials choose to pause, terminate, or divert someone’s progression through the justice system) halved recidivism (re-offending) rates, increased quarterly employment by 53 percent (or 18 percentage points), and increased quarterly earnings by 64 percent. In other words, a person who avoids a felony conviction works almost two more years and earns about $60,000 more than if they had been convicted. While some employers worry about the performance of workers with arrest or conviction records, a five-year study involving almost 500 ex-offenders found lower turnover rates among ex-offenders compared to non-offenders (Paulk, 2016).

Research has also shown that a lack of employment for the formerly incarcerated community members harms national productivity and increases recidivism, racial income inequality, and crime rates (Abraham & Kearney, 2020; Schnepel, 2018). Research has shown that people released from prison into counties during better economic conditions returned to prison at significantly lower rates than individuals released into counties experiencing economic downturns (Yang, 2017). Employment is a key part of returning to and reintegrating into communities—decreasing not only the likelihood of reoffending but also overreliance on public assistance programs. [5] Prior research has focused almost exclusively on private and state employers, while employment in local and Federal agencies for formerly incarcerated persons remains understudied.

Another area of interest to the EEOC is credit history, which may be a factor in suitability determinations, depending upon the risk and sensitivity of the position in question. Credit histories are governed by many of the same processes and rules as criminal histories, especially in the Federal sector. However, criminal histories and credit histories may play different roles in the Federal hiring process than in the private sector, due to a more uniform process for criminal background checks and different potential liabilities, including national security considerations. Since EEOC researchers could not obtain data on credit history, this report focuses solely on the impact of past exposure to the criminal legal system. Despite the lack of data to study the impact of credit histories on the Federal hiring process, many of the patterns and policies considered in the criminal history context have parallels to credit history, as shown in previous research (Bartik & Nelson, 2018; Dobbie et al., 2020).

This report presents evidence that, from 2003 to 2017, the Federal sector may have had higher barriers to employment for formerly incarcerated workers than elsewhere in the economy. However, this report also shows that delaying arrest and conviction record inquiries in the hiring process may provide the EEOC more opportunity to protect these applicants.

A related READD report, Second Chances Part II: History of Criminal Conduct and Suitability for Federal Employment, served to take up the “Next Steps” offered at the end of this present report.

Several laws and regulations govern the use of past arrests or convictions in Federal employment decisions. Federal agencies collect the information to conduct background investigations on their job candidates. The hiring agency enters information concerning the processing of candidates’ investigations is into a centralized database, which is managed by the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency (DCSA). The hiring agency, following the adjudication of information received from the background investigation, reports determinations to Office of Personal Management (OPM). The information collected regarding the prior arrests or conviction is the OPM Form OF-306, which specifically asks: “During the last 7 years, have you been convicted, been imprisoned, been on probation, or been on parole?”

The EEOC has a long history of combating discrimination caused by employers’ use of arrest or conviction records in employment decisions—with decisions dating back to the 1970s. [6] While having a prior arrest or conviction is not a protected category under Title VII, discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin are prohibited. The EEOC has issued multiple policy statements on the appropriate consideration of arrest or conviction records in employment decisions. [7] The most recent and comprehensive of these guidance documents was EEOC Enforcement Guidance, Consideration of Arrest and Conviction Guidance in Employment Decisions, Apr. 25, 2012 ( Arrest/Conviction Guidance). The Arrest/Conviction Guidance clarifies how an employer’s use of an individual’s criminal history in making employment decisions may violate the prohibition against employment discrimination prohibited by Title VII. [8] The Arrest/Conviction Guidance superseded previous EEOC policy statements on using arrest or conviction records in employment decisions and is intended for use “by employers considering the use of criminal records in their selection and retention processes; by individuals who suspect that they have been denied jobs or promotions, or have been discharged because of their criminal records; and by EEOC staff who are investigating discrimination charges involving the use of criminal records in employment decisions” Section II.

The Arrest/Conviction Guidance describes two types of discrimination that can arise from an employer’s consideration of arrest and conviction records: disparate treatment discrimination and disparate impact discrimination. For example, disparate treatment discrimination occurs when an employer rejects a Black applicant based on a prior arrest or conviction but hires a similarly situated White applicant with a comparable arrest or conviction. Title VII requires employers to treat arrest and conviction records the same across protected classes. Disparate impact discrimination occurs when an employer uses policies or practices that do not intentionally discriminate on a protected basis on its face but, as applied, the policy or practice disproportionately screens out people on a protected basis and the policy is not job related or consistent with a business necessity.

Consideration of arrest and conviction records in employment decisions is a hiring policy or practice. For criminal conduct exclusions, relevant information includes the text of the policy or practice, associated documentation, and information about how the policy or practice was implemented. Additional relevant information to consider is “which offenses or classes of offenses were reported to the employer (e.g., all felonies, all drug offenses); whether convictions (including sealed or expunged convictions), arrests, charges, or other criminal incidents were reported; how far back in time the reports reached (e.g., the last five, ten, or twenty years); and the jobs for which the criminal background screening was conducted.” Section V(A)(1).

Black men, in particular, are arrested and incarcerated at rates disproportionate to their numbers in the national population. These national disparities provide a basis for the EEOC to investigate a Title VII disparate impact charge; however, some courts have found that local data can undercut national disproportionalities and make a legal finding of disparate impact less likely at a local level. [9] For example, an employer might present regional data that shows Black men are not arrested/convicted at disproportionally higher rates than White men within the locality in question.

Additionally, employers have an opportunity to show why using a specific policy related to arrest and conviction records is job related and consistent with business necessity. This means that the policy must “bear a demonstrable relationship to successful performance of the jobs for which it was used” and “measures the person for the job and not the person in the abstract.” [10] As detailed in the Arrest/Conviction Guidance, the business necessity defense may be met in two ways:

Best hiring practices should include an individualized assessment of applicants excluded because of past criminal conduct. As the Arrest/Conviction Guidance explains, the following factors are relevant:

Federal employment requires that the employee be reliable, trustworthy, of good conduct and character, and loyal to the United States. In other words, to be hired for a Federal job, an applicant must be deemed suitable. This suitability decision is separate from whether the applicant has the requisite skills and qualifications to perform the job’s tasks. Rather, suitability inquiries assess when the jobseeker’s identifiable character or contacts may have an impact on the integrity or efficiency of their service. This includes questions about an applicant’s honesty, sound judgment, reliability, responsibility, and ability to follow rules. All competitive service positions require a suitability determination whereas excepted service and contractor positions may require a suitability-like determination, referred to as fitness.

There are different levels of investigation based upon the risk and sensitivity level of the position. Low risk positions require less investigation than do public trust (moderate or high risk) and/or national security sensitive positions. The risk and sensitivity level of the position may be relevant to the suitability determination, suitability decisions are handled by the hiring agency. A smaller number of suitability decisions are under OPM’s purview when certain conditions are met or at OPM’s discretion. For instance, OPM may make a suitability decision when there is evidence of an intentional false statement or fraud.

For hiring within the Federal government, the depth of a background investigation is influenced by the tier of the position, with higher tiers getting more scrutiny. Investigative forms have branching questions that only have to be answered in the event of affirmative answers to certain questions. While background investigations at the higher tier include a credit check, the investigation at the lowest tier will not in every instance, it may forgo a credit check for Tier 1 applications that have no other flags. In most cases, the criminal history is checked during the course of the background investigation which is conducted by an authorized investigative service provider. The investigation is not initiated under the individual accepts the conditional offer. After conditional offer, agency may ask applicants about their criminal history, such as via the OF 306. Other agencies might differ slightly in their procedures, but further research, which could be accomplished by surveying those adjudicating hiring within Federal agencies, should be conducted to better understand equity and fairness outcomes of the Federal processes on a systemic level.

Evidence of “criminal or dishonest conduct” is one of eight bases for which an agency can find an applicant unsuitable (5 CFR 731.202(b)(2)). The Declaration for Federal Employment, Optional Form (OF) 306 typically collects this information via two questions:

Additionally, completion of this form requires the applicant to consent to the release of arrest, conviction, and credit information. If an agency makes an unfavorable suitability determination, it may also take a suitability action, following the procedures specified in 5 CFR part 731. Suitability actions by agencies can include cancelation of eligibility, cancelation of reinstatement eligibility, removal, and/or debarment.

The agency in charge of performing background checks has changed in recent years. The National Defense Authorization Act of 2018 mandated that the Department of Defense (DoD) take over the background investigation for its own personnel, in part due to concerns about the accuracy, wait time, and cost of security investigations (Government Accountability Office, 2018; Bur, 2019). OPM delegated to DoD authority to conduct investigations for other agencies for the purpose of determining suitability, fitness, or eligibility to hold a personal identity verification credential to keep background investigation services consolidated with one primary investigative service provider. [13]

Applicants may not appeal an agency’s decision under 5 CFR 332 of “non-selection” (i.e., rescission of a conditional job offer) to the Merit Systems Protection Board. With respect to prior arrest or conviction records, agencies can change an applicants’ determination of eligibility after adjudication (i.e., completing an individualized assessment of the arrest and/or conviction) if there is a foreseeable potential risk in completing the hire. Moreover, the cancellation of a tentative job offer based on an objection under 5 CFR 332.406 is not appealable even if it is based on the criteria for making suitability determinations set forth in 5 CFR 731.202.

The Fair Credit Report Act (FCRA) provides protections to applicants when credit or criminal reports are considered as a basis for denying employment. Under the FCRA, when information from a background report is used in an adverse action against the applicant, the applicant is entitled to know what was in the background report. Applicants also have the right to dispute incomplete or inaccurate information in the background report.

In the Federal process, a number of systems may be queried to assess an applicant’s suitability, including the State Criminal History Repository Check, Credit Check, and the National Crime Information Center/Interstate Identification Index Check. These checks are not foolproof. For instance, studies have shown that 50 percent of arrest records in the FBI’s Interstate Identification Index were associated with arrests that did not lead to convictions—substantially delaying the hiring process and potentially resulting in otherwise qualified candidates missing out on employment opportunities (Nancy et al., 2017). In addition, in any of these queries, there is the possibility of a false positive, or mistakenly flagging someone as having an arrest or conviction record.

In 2016, OPM issued a final rule revising when a hiring agency can request information typically collected during a background investigation for Federal employment (Office of Personnel Management, 2016). The rule became effective in January 2017 with compliance required by March 31, 2017. Like many “ban-the-box” rules implemented by state and local governments, OPM’s rule requires federal agencies to make a conditional offer of employment before it reviews or requests the content of OF-306, the declaration for federal employment form that collects applicants’ background information. [14]

This rule is not absolute. In certain situations, agencies may have a business need to obtain information about the background of applicants earlier in the hiring process to determine if they meet the qualifications or suitability requirements. If so, agencies must request an exception from OPM. OPM will only grant exceptions when the agency shows specific job-related reasons why the agency needs to evaluate an applicant’s arrest, conviction or adverse credit history earlier in the process or consider the disqualification of candidates with prior arrests, convictions or other conduct issues from particular types of positions. [15]

The Fair Chance to Compete for Jobs Act of 2019 (Fair Chance Act) codified OPM’s ban-the-box rule in federal statute and extended the rule’s application to Federal contractors. (Public Law 116–92, 2019). The Fair Chance Act explicitly covers almost all executive agencies (including cabinet agencies and the U.S. Postal Service, but not the armed forces), the legislative branch, and the judicial branch of the Federal Government (other than judges, justices, and magistrates). It also applies to civilian agency and defense contractors. Finally, it requires each agency to establish a complaint and appeal procedure for violations of the Fair Chance Act. [16]

Ban-the-box started as a grassroots policy supported by nonprofit organizations like All of Us or None and the National Employment Law Project (NELP). These policies aim to encourage employers to hire formerly incarcerated workers by removing arrest and conviction inquiries from the job application. Ban-the-box proponents hoped to increase applications from formerly incarcerated job seekers and encourage employers to make individualized assessments rather than categorical exclusions of these community members. For example, employers would evaluate each prior arrest or conviction by considering the age of the offense and its relevance to the job at hand. This also allows applicants to present evidence of rehabilitation and review background checks, giving them a chance to “get a foot in the door” and not be prejudged by a prior arrest or conviction. By humanizing the applicant and encouraging the employer to assess work-readiness, ban-the-box policies aim to minimize discrimination against applicants with an arrest or conviction record as a class (Avery & Lu, 2020).

Ban-the-box refers to a wide range of policies, so defining terms is helpful. All ban-the-box policies require the affected employer to delay inquiring about previous arrests or convictions, although the length of the delay varies by specific policy. Some policies may require a conditional job offer, while others just require removal from the initial application. The nature of these policies depends, in part, upon the employer enacting it. Ban-the-box policies have been implemented at the state level by state executives and legislatures. Similarly, many cities and counties have chosen to implement similar policies.

Employer coverage also varies with different ban-the-box policies. Ban-the-box has been applied to Federal, state, and local government employers, contractors, and private employers. In September 2020, NELP found that “a total of 35 states have adopted statewide laws or policies applicable to public-sector employment” and estimated that over three-fourths of the U.S. population lived in a jurisdiction that has some version of ban-the-box, illustrating the broad scope of the policy.

However, there is considerable variation across policies. For instance, Arizona’s ban-the-box executive order (Arizona Executive Order 2017-07) applies just to employment in the executive branch, whereas Delaware passed legislation (Delaware House Bill 167 (2014)) that applies to all public employees including the state agencies and political subdivisions, such as cities and counties. Many states have also implemented ban-the-box policies for contractors, as have 36 non-state jurisdictions (including the District of Columbia). In addition, 14 states and 20 localities have applied ban-the-box laws to private employment. The degree to which certain private employers might be exempt varies by state, but policy implementation is broad.

Critics of ban-the-box policies, such as the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB), see such laws as unnecessarily masking important information that might impact the safety of the business, work projects, and customers. Critics also argue that ban-the-box laws generally make the hiring process more difficult to navigate for both applicants and employers. Some employers, for example, report that they would rather avoid making offers that they will later have to rescind. And employers who hire in multiple jurisdictions may have to navigate many varying ordinances. NFIB’s chief executive has argued that “ban-the-box laws make it harder for employers to talk about a criminal record at a time that is convenient for them, this means that a small-business owner may spend hours, days, or even weeks going through the hiring process only to find a worker is unqualified” and that employers have legitimate reasons for preferring to inquire about arrest and conviction records early in the hiring process (Maurer 2018).

Another critique of ban-the-box policies is that they may encourage more direct racial and ethnic discrimination against Black and Latino job seekers. If employers would rather avoid extending offers to workers with past arrests or convictions but are unable to directly learn this information, then employers may turn to observable proxies for criminal history. While ban-the-box policies may combat racial animus or inaccurate prejudices by encouraging more interpersonal connection with a given applicant, it is unlikely to eliminate other reasons for excluding formerly incarcerated applicants from jobs (e.g., statistical discrimination, legal requirements, or negligent liability concerns). More specifically, if certain traits, such as race, gender, age, education, work experience, residency, or other factors correlate with rates of arrests or convictions, employers may begin to favor groups within those metrics that have lower average criminal justice exposure (Raphael, 2021). Thus, critics argue that while ban-the-box is well-intended, the statistical discrimination that results harms young Black men with limited educational attainment—including those who do not have any arrest or conviction histories (Doleac, 2019). Critics also argue that the harm to this group outweighs the potential benefits from ban-the-box policies. However, given the hiring structures implemented in the Federal sector, such as a formal adjudication process, it is possible that some of these concerns may be mitigated in practice. [17]

The Federal sector has implemented ban-the-box policies in different forms over time. Given current data availability, it is difficult to assess how successful these policies have been in increasing Federal employment opportunities for people with arrest or conviction records. As such, it is also too early to evaluate the potential impact of the Fair Chance Act’s expansion of ban-the-box protections to Federal contract workers in December 2021.

While not perfectly analogous, some lessons can be drawn from the EEOC’s experience enforcing Title VII’s protections against the discriminatory use of arrest and conviction records in private and state and local government settings. Ban-the-box policies may influence Title VII enforcement in a variety of ways:

The purpose of this report is to determine the impact of prior arrests and/or convictions on an applicant’s ability to obtain employment with the Federal government.

This report uses nationally representative surveys to estimate the number of Federal workers with arrest or conviction records. Specifically, this report used a sample from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), which collects information about people’s past behavior over time. This sample consisted of almost 40,000 people and covered the years 2003-2017. [19] The PSID is funded by the National Science Foundation and collects data continuously on employment, income, wealth, expenditures, health, marriage, childbearing, child development, philanthropy, education, and numerous other topics, including exposure to the criminal legal system. A related data source, the Transition to Adulthood Supplement (TAS), was used to expand analysis. The TAS follows all PSID sample children who are entering early adulthood, and who comprise the future focal sample members of Core PSID.

There are some drawbacks to this methodology. For one, the number of people in the PSID with past exposure to the criminal legal system is relatively small (885 people). As such, this report’s estimates may not be representative of the population as a whole. Also, the type of data collected by the PSID makes it hard to accurately count the number of individuals in the survey who may have been incarcerated. [20] Indeed, the present analysis may understate the challenges faced by individuals with exposure to the criminal legal system because data linking them to specific labor market outcomes are lacking and can be unreliable. Efforts are underway to improve data availability, which may increase the accuracy of future research. (See “Policy recommendations to facilitate further research” on page 17).

Data from the PSID suggests that, from 2003 to 2017, people who were previously incarcerated were less likely to be Federally employed than people without such records. According to the PSID, about 3.3 percent of all respondents reported having been (or currently being) Federally employed. However, only 1.8 percent of respondents who had been previously incarcerated reported being Federally employed. In other words, between 2003 and 2017, respondents with who has been previously incarcerated were about half as likely to be Federally employed compared to those without records (Figure 1). This gap suggests that there were roughly 300,000 fewer Federal applicants with workers than expected during this time period. [21]

Figure 1: Probability of Federal Employment

Source: U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission using data from the University of Michigan, Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID).

Respondents with prior records of incarceration may differ from those without records across many dimensions. For a variety of reasons, including systemic disparities in the criminal legal system, PSID respondents with prior records are more likely to be male, Black, and have lower educational attainment. If the probability of Federal employment varies across these factors, it is possible that these factors (rather than differences in incarceration records) explain the different hiring rates between the two groups (a phenomena sometimes referred to as omitted variable bias). This study uses linear regression to isolate the correlation between having a record of incarceration and Federal employment. A regression calculates the association between the outcome (dependent) variable and each explanatory (independent) variable, when all other explanatory variables are held constant. The results of a regression include coefficients for each explanatory variable that quantify the magnitude and direction of the relationship between the outcome variable and the corresponding explanatory variable. The results suggest that workers with records of incarceration are less likely to be Federally employed. These results hold regardless of the particular statistical specification.

Column 1 of Table 1 displays the coefficients from a regression that sets Federal employment within the past two years as the dependent variable and an indicator for prior incarceration as the only explanatory variable. Results show that 3.3 percent of surveyed workers without arrest or conviction records were Federally employed. Federal employment for workers with arrest or conviction records was 1.5 percentage points lower. The coefficient on arrest and conviction history was statistically significant with a p-value less than .001, meaning that it is very unlikely (at the 0.1 percent significance level) to be purely by chance. This means that PSID respondents with prior records of incarceration were almost 50 percent less likely to be Federally employed compared to similarly situated respondents without such records.

Column 2 accounts for whether or not the respondent is currently working. Currently employed respondents were 1.4 percentage points more likely to have Federal jobs within the past two years. Workers with a record of incarceration were less likely to be working overall (and working at all is a precondition for working Federally). Including whether the respondent is currently working allows for a comparison between respondents who are similarly attached to the labor force. After controlling for whether or not a respondent was currently working, the respondents with records were still 1.3 percentage points less likely to be Federally employed. This figure is statistically significant. This means that PSID respondents with records of incarceration were almost 30 percent less likely to be Federally employed compared to similarly situated respondents without such records.

Column 3 controls for an array of additional factors measured in the PSID. Column 3 effectively compares individuals who are similar in their current work status; years of education; age; residency in states with similar unemployment and wage rates; survey response year; and are of the same race, sex, and state of residence. After controlling for all these factors, respondents with records of incarceration were 1.5 percentage points less likely to have been Federally employed. This means that PSID respondents with records of incarceration were almost 50 percent less likely to be Federally employed compared to similarly situated respondents without such records.

Column 4 looks at changes in individuals over time and at Federal employment before and after a given individual was incarcerated. After a respondent developed an record of incarceration, they were found to be 1.9 percentage points less likely to be Federally employed.

Column 1: Past 2 Years

Column 2: Working

Column 3: Comparators

Column 4: Before and After Contact